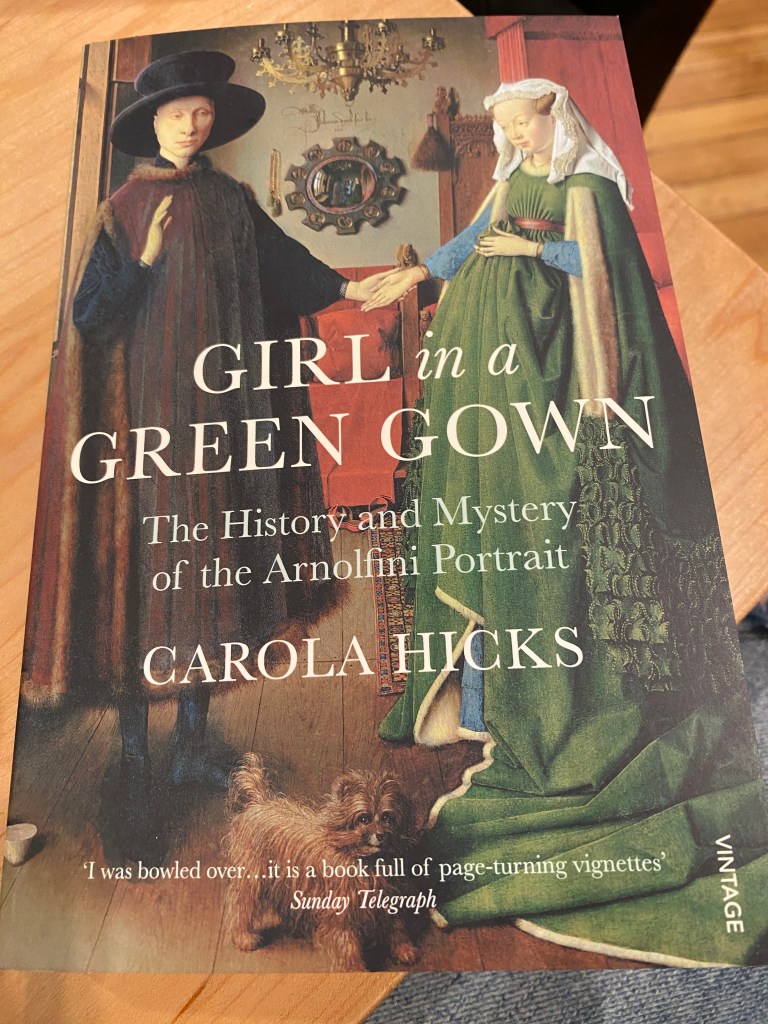

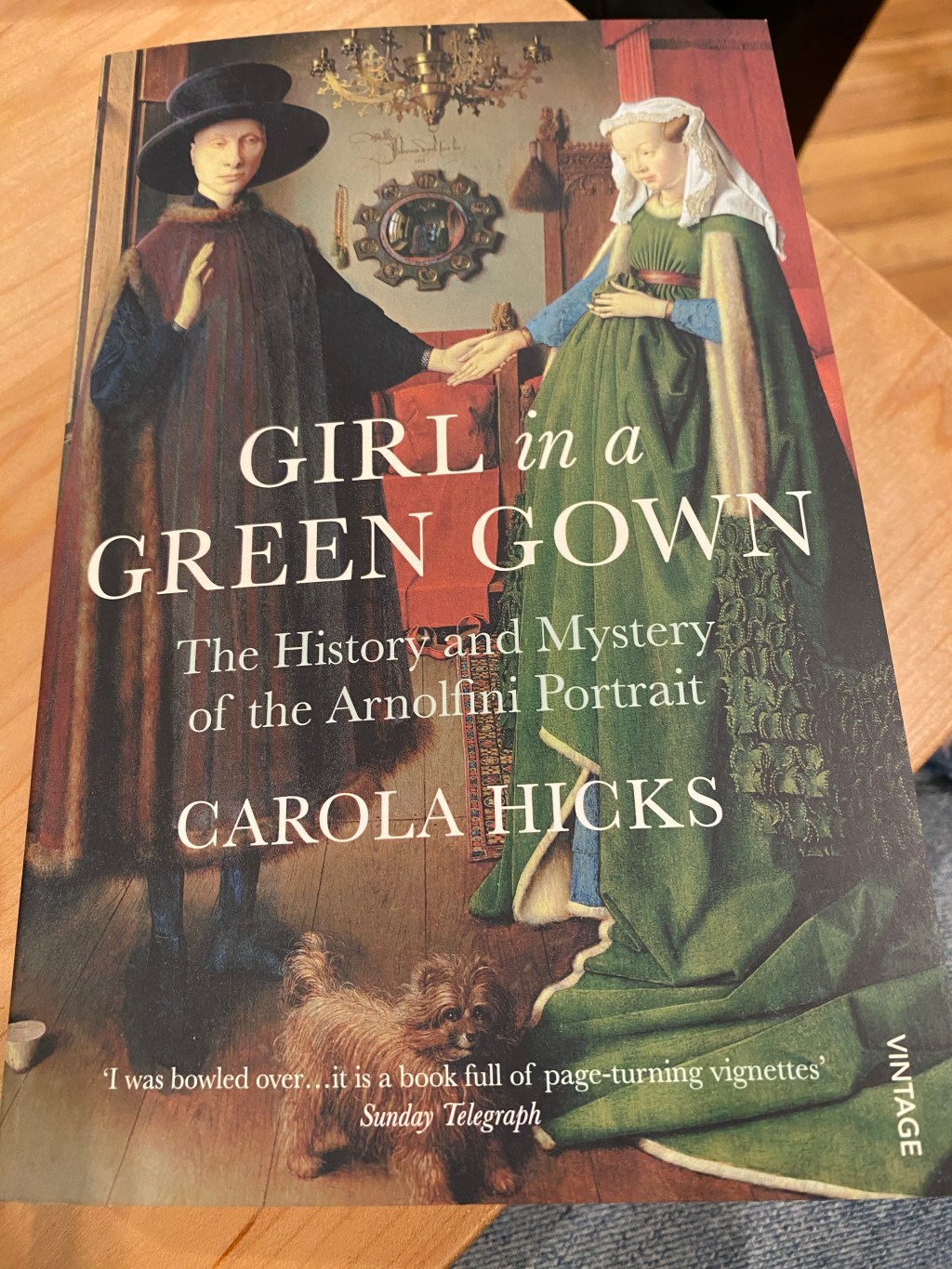

The Girl in the Green Gown: The History and Mystery of the Arnolfini Portrait by Carola Hicks

My mom bought me this book at the Gallery bookstore, and it’s worth a read. Hicks died just as the book was being finished, and her husband completed it. Its alternating chapters cover the history of the painting and its intriguing elements – the red shoes, the green gown, the oranges, the mirror. It’s full of fascinating vignettes and deep research.

The double portrait on oak is from 1454 and entered the Gallery’s possession in the early 19th century as one of the first works purchased. It passed from its original owners to a court employee as well as a series of royals until it ended up looted at the Battle of Vitoria in 1813 when its then owner, Joseph Bonaparte, fled. While the English made an effort to repatriate stolen items, a provenance was eventually constructed with the help of an English dealer, and the item was sold.

While van Eyck was a court employee, this painting was a commission, and the clever details in the painting are clues to the social status and wealth of the subject. The Arnolfini family were traders from the Lucca region of Italy, and the Netherlands was a bustling trading region. Many of the colors and items in the painting speak to the power of world trade.

The man wears a dark purple houppelande lined in fur, woolen stockings, and rich leather shoes. The shoes were so precious that his wooden oversoles, designed to protect the shoes when outdoors, lay nearby. The lady’s shoes are tossed in the background, and the deep red color of the leather along with the red bedding and seating material are a clue to their wealth as kermes, a safe and color fast red dye, was derived from the dried bodies of an insect living in the Mediterranean. The window to the left includes glass, an expensive fascination at the time, and on the windowsill sit some oranges, an imported delicacy. While her green overcoat was a less expensive color to dye, it is lined in fur, which Hicks speculates was white squirrel, simply a squirrel harvested in the winter when its fur turned white. A brush and an amber paternoster, think rosary but a single strand, hang on the wall.

The paints would have been oil, and van Eyck is mistakenly credited as the first to paint with the substance. He was not. Paints would have been mixed individually and covered with pigs stomachs to keep them from drying. Layers of paint could be applied over time with the individual layers requiring extensive drying time. The blue paint used in her undercoat was expensive to purchase as it came from lapis lazuli, a deep blue metamorphic rock found in Afghanistan. Hicks notes that the terms of the portrait contract probably specified authentic paints and other such minutia.

Infrared dating done at the National Gallery in the years since the purchase in 1842 has confirmed the underlying sketch and how van Eyck creatively changed the composition to give the man a bigger hat and change the position of the rug and the angle of the woman’s eyes. Hicks notes that the woman is so similar to other women in his work that she may have been a composite or template along with the items in the room, which are found in his other works.

Then there is the mirror. It’s also a clue to their wealth as mirrors were not well known outside royal homes, and this one includes small vignettes with the stations of the cross while also reflecting the room back to the viewer revealing the visitors that the couple was welcoming into their reception area. The dog doesn’t appear on the initial sketch and may have been a last minute addition. It’s a Brussels Griffon, a breed native to the area.

This is a fascinating and readable book that does some justice to this remarkable painting. If you’re in London, it’s a must see.