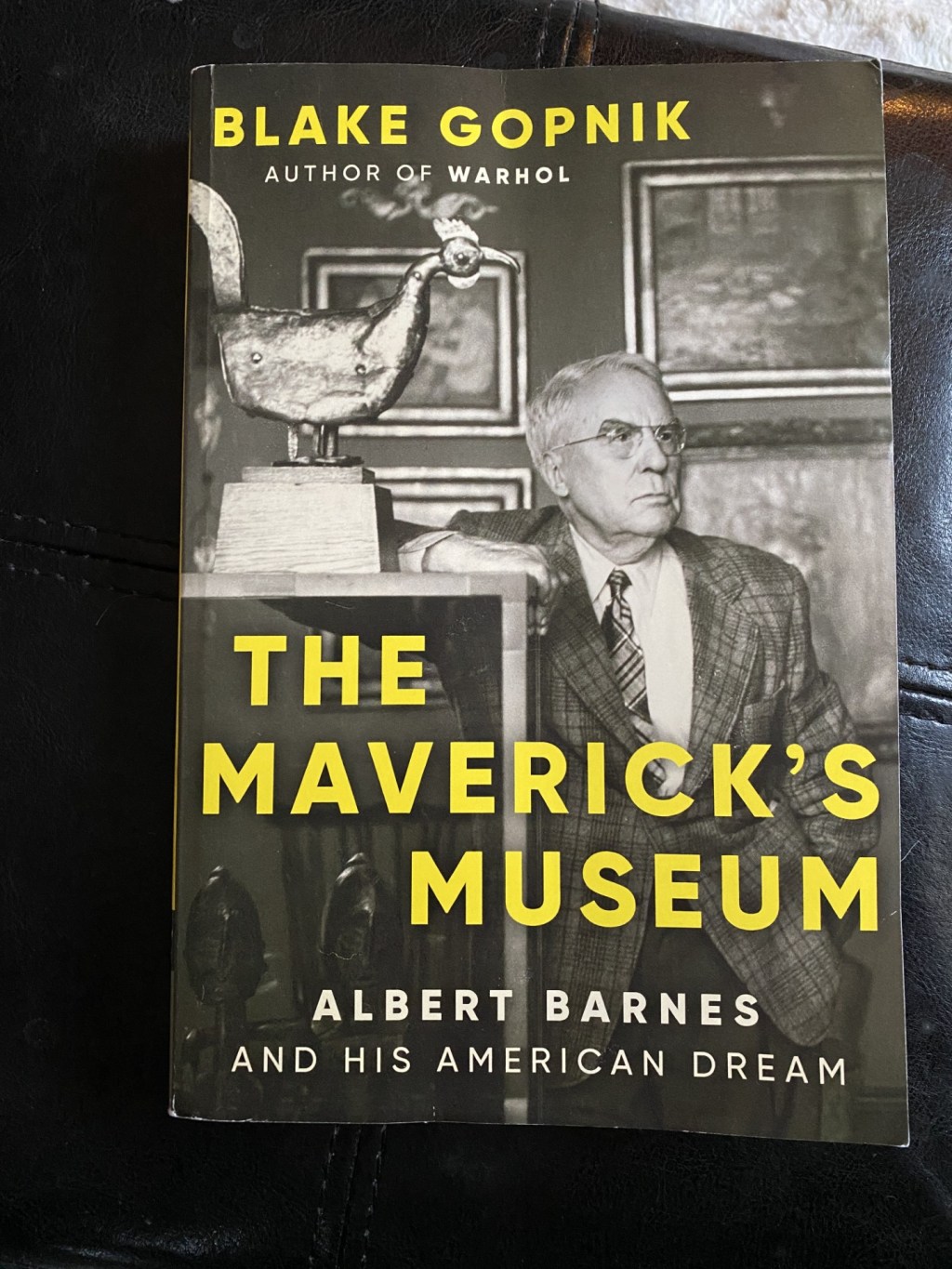

Blake Gopnik

The Maverick’s Museum: Albert Barnes and His American Dream

I read Gopnik’s tome Warhol during the pandemic and really loved it. It’s comprehensive and yet readable, so I was eager to start this shorter volume on the mercurial chemist and his temple of art in Merion. It did not disappoint.

Trained as a physician but unsuited to the human interaction involved in practicing, Barnes drifted to chemistry and struck gold with Argyrol, a drug widely used to prevent gonorrheal blindness and other pathogenic bacterial and viral infections to the eyes of infants that is still used today. Barnes partnered with German chemist Dr. Herman Hille, and Gopnik notes that credit for the actual chemistry seems in doubt. What isn’t in question was Barnes relentless and successful marketing, which included bribing scientific publications to blurb and promote the drug. The two paired to form their own company until Barnes’ brute nature fractured the relationship for good and he took sole ownership. He sold the company in 1929, one of many fortunately timed events for him.

Gopnik notes that Barnes’ business sense merged with his innate liberalism as he constructed a racially and gender diverse workplace, which was unusual for the time. He also hung his art in his factory and, for a time, ran art and educational classes for his staff. Two of his female employees would go on to prominent positions in the Barnes Foundation despite having little more than a high school education. Barnes valued loyalty.

In addition to cars, Barnes began collecting art in 1911 buying the art of a personal friend, William Glackens. Soon he was sending friends to Paris to buy more with one of Van Gogh’s 1889 Postman paintings being an early purchase. (I adore that painting.) Having started collecting, Barnes went about creating a philosophy of art with the inspiration of a new and lifelong friend, philosopher and pragmatist John Dewey. This is the only part of the book that felt bogged down for me – the enormous space devoted to how Barnes looked at the work, his hours devoted to writing about his philosophy, and his relentless bullying of those that didn’t see it his way. Browbeating, angry letters, sarcasm, and grudges over slights big and small were hallmarks of his life.

It’s some consolation that in the very last chapter Gopnik notes that the current Barnes Foundation doesn’t adhere to its founder’s obsessiveness.

And speaking of the current Foundation, it is now in Philadelphia proper having moved from Merion after a protracted battle with the Commonwealth of PA over its tax exempt status and its suburban neighbors over traffic. The new building is a replica of Barnes original vision with small rooms laid out as he planned complete with ironwork and other primitives flanking the paintings. It even includes the Matisse mural specially constructed for the original space.

It’s the largest collection of Renoir anywhere in the world.

Of the art himself, Gopnik notes that Barnes had a taste for the late Renoirs with more extensive nudity–ones with “enormously fat women with very small heads” as Mary Cassatt noted to Renoir himself. At Barnes’ direction, one such piece hangs next to Cézanne’s The Cardplayers, a masterwork of fully-clothed men in a masculine space. Gopnik noted, Those late Renoirs depict, “Apollonian everyday of the collector’s imagination, which flees from the real everyday of conflict that he built for himself.” #recommended